Part 1 of this series outlined the history of the Zionist project from the late 19th century until the creation of Israel in 1948 with its attendant expulsion of Palestinians in the Nakba. Part 2 discussed the creation of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, its guerilla campaign of cross-border raids from Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon, and the blowback it received both from the Israelis and its Arab hosts. This phase took a decisive turn in 1982 when Israel invaded southern Lebanon, with massive loss of Lebanese and Palestinian lives, and the PLO was ejected from Lebanon.

The Israelis were highly satisfied with what they had achieved with the Lebanese invasion, thinking they had dealt a decisive blow to Palestinian resistance. This wasn’t how it worked out, as Rashid Khalidi tells us.

|

| A modern David and Goliath |

The intifada (an Arabic term for ‘uprising’ or ‘shaking off’) was a spontaneous, bottom-up campaign of resistance, born of an accumulation of frustration and initially with no connection to the formal political Palestinian leadership. As with the 1936-39 revolt, the intifada’s length and extensive support was proof of the broad popular backing it enjoyed. The uprising was also flexible and innovative, developing a coordinated leadership while remaining locally driven and controlled. Among its activists were men and women, elite professionals and businesspeople, farmers, villagers, the urban poor, students, small shopkeepers, and members of virtually every other sector of society. Women played a central role, taking more and more leadership positions as many of the men were jailed and mobilising people who were often left out of conventional male-dominated politics.

Along with demonstrations, the intifada involved tactics ranging from strikes, boycotts, and withholding taxes to other ingenious forms of civil disobedience. Protests sometimes turned violent, often ignited by soldiers inflicting heavy casualties with live ammunition and rubber bullets used against unarmed demonstrators or youths throwing stones. Nevertheless, the uprising was predominantly nonviolent and unarmed, a crucially important factor that helped mobilise sectors of society in addition to the young people protesting on the streets while showing that the entirety of Palestinian society under occupation opposed the status quo and supported the intifada.

Israel’s response, directed by Yitzhak Rabin as Defence Minister, was harsh and violent, aimed at suppressing the Intifada by intimidation and violence. However, this meant that for the first time global sympathy began to swing towards the Palestinians, with images such as that of a young Palestinian with a stone confronting an Israeli tank providing a true indication of the imbalance involved in the conflict. Israel was shown up as a brutal occupying power rather than, as Israelis preferred, a vulnerable democracy surrounded by powerful and implacable enemies.

This led to a change for the PLO. It had suffered a massive military defeat, effectively signaling the end of its (flawed) strategy of armed resistance. At the same time, others had taken up the banner of resistance, leaving the PLO more marginalised in its increasingly distant exile. In response its leaders made a massive shift – they renounced armed struggle, recognised Israel’s right to exist, and entered into negotiations based on the idea of a Palestinian state in the occupied territories.

This opened the way for a series of diplomatic negotiations which became known as the ‘Oslo peace process’, a set of talks between Israel and the PLO (initially as part of the Jordanian negotiating team as Israel refused to deal directly with them) brokered by the US. Reflecting the relative weakness of their negotiating position, the PLO ceded a lot of ground as a precondition for admission to the talks. They did not insist on the terms of either UN Resolution 181 from 1947, which specified an Arab state in Palestine alongside the Jewish state of Israel, or Resolution 194 from 1948 which specified the return of refugees. They also accepted a subtle rewording of Security Council Resolution 242 which linked Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories to treaties and security guarantees between Israel and the Arab nations – the Oslo process saw the PLO accepting a reference to ‘territories occupied’ rather than ‘the territories occupied’, leaving open the possibility that not all the territories would be handed back.

Khalidi acted as an advisor to the delegation, firstly in Madrid and later in Washington. There ended up being two separate negotiations, one in Oslo and the other in Washington, and the final Oslo Accords were signed without consultation with the Palestinian negotiators in Washington.

When we first saw the text of what had been agreed in Oslo, those of us with twenty-one months of experience in Madrid and Washington grasped immediately that the Palestinian negotiators had failed to understand what Israel meant by autonomy. What they had signed on to was a highly restricted form of self-rule in a fragment of the occupied territories, without control of land, water, borders, or much else. In these and subsequent accords based on them, in force until the present day with minor modifications, Israel retained all such prerogatives, indeed amounting to almost complete control over land and people, together with most of the attributes of sovereignty….

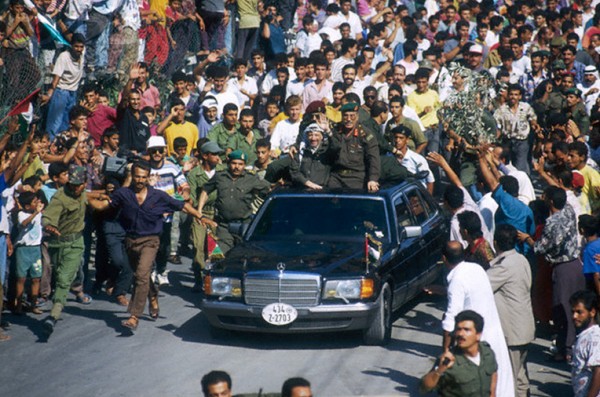

Yasser ‘Arafat returned to Palestine in July 1994 and I visited him soon after in his new headquarters overlooking the sea in Gaza. He was ecstatic to be back in his homeland after nearly thirty years and to have escaped from the gilded cage that had been his lot in Tunis. He did not seem to realise that he had moved from one cage to another. I had come to express my deep concern about the deteriorating situation in Arab East Jerusalem, where I had been living. Israel had closed the city off to Palestinians from the rest of the Occupied Territories and had begun erecting a series of walls and massive fortified border checkpoints to regulate their entry… ‘Arafat brushed aside my concerns. I soon realised that my visit was a waste of time. He was still afloat on a wave of euphoria, enjoying the homage of worshipful delegations from all over Palestine. He was in no mood to hear bad news, and in any case, he airily indicated, any problems would soon be resolved.

Khalidi didn’t visit ‘Arafat again until 2002, when he was besieged in Ramallah, literally in a cage, unwell and defeated. The exile was over but the war continued, as we will see in the next part of the series.

|

| 'Arafat's triumphant return proved a false dawn for peace in Palestine |

Comments