In Part 1 of this series I provided a quick precis of the emergence of Zionism and its adoption by the British in the administration of Palestine between the two World Wars, concluding with the Nakba – the ‘catastrophe’, in which over 700,000 Palestinians were forcibly expelled from Palestine - and the creation of Israel in 1947-48.

In October 1953, Israeli forces in the West Bank village of Qibya carried out a massacre following an attack by feda’iyin that killed three Israeli civilians, a woman and her two children, in the town of Yehud. Israeli Special Forces Unit 101, under the command of Ariel Sharon, blew up forty-five homes with their inhabitants inside, killing sixty-nine Palestinian civilians. The raid, which was condemned by the UN Security Council, was launched despite the unceasing efforts of Jordan (then in control of the West Bank) to prevent armed Palestinian activity, which included imprisoning and even killing would-be infiltrators.

In 1956 Israel used the Suez Crisis as justification for an invasion of Egypt, with the approval of France and Britain.

As the occupying Israeli troops swept through the Gaza towns and refugee camps of Khan Yunis and Rafah in November 1956, more than 450 people, male civilians, were killed, most of them summarily executed (according to a UNRWA report)…. The civilians were killed after all resistance had ceased in the Gaza Strip, apparently as revenge for the raids into Israel before the Suez war…. (T)he gruesome events in the Gaza Strip were not isolated incidents. They were part of a pattern of behaviour by the Israeli military. News of the massacres was suppressed in Israel and veiled by a complaisant American media.

This represented a dilemma for the Arab nations which hosted Palestinian refugees. On the one hand, they had no love for Israel, and their citizens were firmly behind the Palestinian cause. On the other hand, Palestinian raids across their borders represented a serious risk to them, given their relative military weakness compared to the Israelis. In addition, the presence of armed Palestinian militias in their nations threatened to destabilise their own regimes, providing a potential source of resistance along with more localised dissident forces.

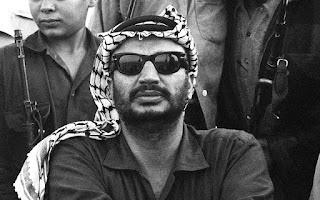

|

| A young Yasser 'Arafat |

The creation of this more disciplined, centralised body was not enough to save the Arab nations. In June 1967 Israel launched a ‘first strike’ simultaneously on Egypt, Jordan and Syria, following various cross-border raids by Palestinian militants and the increasing support of these raids by the nationalist governments of Syria and Egypt. The final straw was Egypt moving troops to the Sinai Peninsula and expelling UN peacekeepers.

Israel portrayed itself internationally as a tiny nation threatened by powerful, militant neighbours. In fact the opposite was the case. Western intelligence suggested that the Egyptian move was largely posturing and that there was no indication of an impending invasion. Thanks to British and French military aid Israel had overwhelmingly superior military resources and their first strike effectively wiped out the air forces of the three countries, facilitating a rapid ground invasion. Israel gained control of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) which had been part of Jordan, the Gaza Strip which had been part of Egypt, and the Golan Heights which was part of Syria. Israel continues to control all three territories – Golan Heights was effectively annexed by Israel in 1981 and its residents offered citizenship, while the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza remain ‘occupied territories’.

The diplomacy around the 1967 war represented a substantial shift in the international alignments in the Middle East. The US had up until then tried to be something of an ‘honest broker’ between Israel and the Arab nations and Israel had relied most heavily on British and French support. After 1967 the US shifted decisively to Israel’s side and the British and French steadily disengaged. This change was largely driven by the US focus on the Cold War with the USSR - Egypt and Syria were seen as Russian proxies and Israel as a reliable US ally.

The large Palestinian populations on Gaza, West Bank and East Jerusalem were now under Israeli occupation, and Beirut and Southern Lebanon became the hub both of the PLO and of Palestinian culture more broadly, with a resurgence of literature and the arts along with political consolidation. This cultural renaissance provided a major boost to the idea of Palestinian identity and nationality, deepening this beyond mere political militancy. However, the militancy did not go away, with the PLO launching frequent raids from Lebanon into northern Israel.

|

| Ariel Sharon |

During the ten weeks of fighting from early June, through to mid-August 1982, according to official Lebanese statistics more than nineteen thousand Palestinians and Lebanese, mostly civilians, were killed and more than thirty thousand wounded. The strategically located ‘Ain al-Hilwa Palestinian refugee camp near Sidon, with over forty thousand residents, was almost entirely destroyed after its population offered fierce resistance to the Israeli advance. In September a similar fate befell the twin Sabra and Shatila camps in the Beirut suburbs, scene of an infamous and grisly massacre after the fighting had supposedly ended. Beirut and many other areas in the south and the Shouf Mountains sustained severe damage, while Israeli forces periodically cut off water, electricity, food and fuel to the besieged Western part of the Lebanese capital as they intermittently, but at times very intensively, bombarded it from air, land and sea. The official Israeli toll of military casualties during the ten weeks of war and siege totalled more than 2,700, with 364 soldiers killed and nearly 2,400 wounded. The invasion of Lebanon and the subsequent lengthy occupation of the southern part of the country – which ended only in 2000 – involved Israel’s third-highest military casualty toll among the six major wars in its seventy-plus-year history.

The aim of this invasion, at least for Sharon, was not merely to stop PLO attacks from Lebanon. Since the country was also the PLO’s base, it was designed to weaken the organisation everywhere and particularly in the occupied territories, making it easier for Israel to annex them.

Khalidi and his family were in Lebanon at the time of the invasion, with Khalidi teaching at the university, his wife (pregnant with their third child) working as editor of the Palestine News Agency’s English language bulletin and their two young daughters in kindergarten and nursery school. They were forced to flee to safety amidst heavy bombardment and spent the siege together, along with other family members, in their apartment block in West Beirut, continuing to edit the bulletin and providing information from within the city to Western journalists.

Toward the end of the siege, on August 6, I was near a half-finished eight-story apartment building a few blocks from where we lived when a precision-guided munition demolished it. I had stopped to drop off a friend at his parked car not far from the building. I had almost reached home as the planes swooped down, and I heard a huge explosion behind me. Later I saw that the entire building was flattened, pancaked into a single mound of smoking rubble. The structure, which had been full of Palestinian refugees from Sabra and Shatila, had reportedly just been visited by ‘Arafat. At least one hundred people, probably more, were killed.

He then recounts the massive diplomatic and financial support provided by the US to Israel, and the passivity of the Arab governments who issued statements condemning the invasion but took no action and were easily fobbed off by the ‘Reagan Plan’. This plan was a diplomatic initiative which proposed a limit on Israeli settlements in Palestinian territory and a Palestinian authority. The Israeli government never agreed to it and the US never insisted. General Arab opinion was strongly on the Palestinian side but public pressure wasn’t enough to make their undemocratic governments act. Nor was there unalloyed support for the PLO even among ordinary Arabs.

While the PLO knew it could expect little support from the Arab regimes in power in 1982, the organisation had counted on a sympathetic response from the Lebanese people. However, the PLO’s heavy-handed and often arrogant behaviour in the preceding decade and a half had seriously eroded popular support for the Palestinian cause in general and especially for the Palestinian presence in Lebanon. … Palestinian operations in Lebanon were supposedly constrained within a formal framework – the Cairo Agreement, adopted in 1969 – which had given the PLO control of Palestinian refugee camps and freedom of action in much of South Lebanon. But the heavily armed PLO had become an increasingly dominant and domineering force in many parts of the country… The creation of what amounted to a PLO mini-state in their country was ultimately unsustainable. There was also deep resentment of the devastating Israeli attacks on Lebanese civilians that were provoked by Palestinian military actions.

All this ultimately meant there was not much resistance to the PLO being ejected from Lebanon altogether and they ended up basing themselves in Tunis with very limited scope for action.

Nor was this kind of miscalculation a one-off event. The PLO had already got itself expelled from Jordan as the kingdom sought peace with its Israeli neighbours, impossible with ongoing Palestinian raids launched from its territory. When the Iraqi government launched its invasion of Kuwait in 1989 the PLO publicly supported Iraq. This made a kind of sense, since Iraq was a major backer of the PLO. However, there were several hundred thousand Palestinians living in Kuwait who had complete freedom provided they didn’t get involved in local politics. The PLO’s stance meant that after the US drove the Iraqis from Kuwait the Palestinians were expelled. The PLO leadership found themselves increasingly isolated and restricted.

Khalidi is highly critical of ‘Arafat and the PLO leadership. He suggests that the PLO forces under them were undisciplined and corrupt and got away with crimes up to an including murder with no consequences. He also suggests that while they were comfortable playing the game of Arab political intrigue (despite various missteps) they made no attempt to win over public opinion on the West even though this was crucial to shifting the US and European powers towards them. The leadership had little understanding of democratic governance and so Israel, with a sophisticated Western propaganda operation, was left unchallenged in these countries.

They were also left with limited opportunities to exercise diplomacy, because the Israeli government, backed by the US, consistently refused to deal directly with them and insisted on pre-conditions for any negotiation which essentially meant giving up most aspects of the aspiration for Palestinian nationhood. They appeared to have nowhere else to go. However, this did not necessarily clear the way for Israel, who soon discovered the Law of Unintended Consequences, as I discuss in Part 3.

Comments