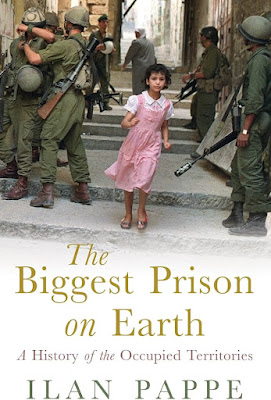

Following reading and writing for my series of posts on the long-running war on Palestine, I followed up on a recommendation from a friend* to have a look at Israeli historian Ilan Pappe and read his book, The Biggest Prison on Earth: A History of the Occupied Territories, published in 2017.

Ilan Pappe was born in Haifa, Israel in 1954, and studied and taught history at the University of Haifa. However, his writings led to personal attacks in the media and threats to him and his family, so he left Israel and now teaches at the University of Exeter in the UK. To say he's not a fan of Zionism is an understatement. He is on record as supporting a unitary state in Palestine in which Jews and Palestinians have equal citizenship, and the right of return for the descendants of Palestinian refugees of the Nakba.The Biggest Prison on Earth examines the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza since the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. But first of all he provides a quick summary of the material covered in his earlier book, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. He argues that the Nakba in 1947-48 was a systematic program of ethnic cleansing, designed to ensure not only that the Jewish state of Israel controlled most of Mandatory Palestine, but that Jews would retain a secure demographic majority. As a result over 700,000 Palestinians - three quarters of the Palestinian population - were expelled to the surrounding nations and the newly created nation of Israel took control of 78% of the area covered by the former British Mandatory Palestine.

The Zionists would have liked to take over control of the whole of Palestine, but for diplomatic reasons they left the West Bank in the hands of Jordan and Gaza as part of Egypt, as well as the Golan Heights controlled by Syria. This meant that they saw their nation-building project as incomplete - there was still land that they saw as rightfully 'theirs' which they didn't control. Once they had consolidated their control of their initial land-grab, they started making plans for expansion. As early as 1963 they initiated concrete plans for an occupation of the remaining territories, war-gaming an invasion, devising a legal framework for an occupation and appointing a shadow 'administration in waiting'.

The pretext finally came in 1967 with an escalation of tensions with Egypt and Syria and military posturing by both countries. In June 1967 Israel launched pre-emptive attacks on Egypt, Syria and Jordan, using its superior firepower to disable their air forces and then invade all three countries. At the end of six days of hostilities the Israelis were firmly in control of the Golan Heights, the West Bank and Gaza.

So now the Zionists in Israel had, in a sense, achieved their goal, controlling the final 22% of the original mandatory territory. However, this control brought with it around a million resident Palestinians in the West Bank and another 450 thousand in Gaza, many of them refugees from 1948. This revived the long-standing Zionist concern with demographics. If all these people were to become citizens of Israel they would be a significant political force and have the potential to upend the Zionist project. Unless the territories were to be returned to their Arab rulers - something the Israeli government never seriously considered - there were two options. One was to expel the existing residents as they had in 1948, but such a mass expulsion in 1967 would have risked the support of their key international supporters.

This meant they were left with the second option, a policy which Pappe describes as the creation of a giant, open-air prison. Palestinians were presented with a choice, what Israeli authorities describe as 'carrot and stick', as if Palestinians are livestock. If they behaved themselves and meekly accepted what they were offered, they would be allowed to live in an 'open prison', able to leave to work in Israel and have a measure of freedom within their own lands, but no citizenship or stake in the State of Israel. If they resisted, they would find themselves in the equivalent of a maximum security prison, with lock-downs, curfews, arbitrary detention and searches and confiscation of property. These punishments would be able to be presented to the wider world as their own fault for engaging in 'terrorism'.

The territories were, in terms of international law, 'occupied territory'. However Israel never made any pretence of following international law applying to such an occupation. This legal framework includes the notion that occupation is short-term, that there is to be no significant property takeover, that the occupying power is not to resettle parts of its own population in the occupied territory, that there is to be the least possible interference in local social and economic life, and that the occupier must move as soon as possible to return control to a local civilian government.

None of these things happened in the West Bank and Gaza. For a start, Israel has essentially imposed a blockade on both territories. They are prevented from exporting to or importing from surrounding nations, creating a monopoly for Israeli products. They also allowed Israelis to establish 'settlements' (as they are usually named, although 'colonies' would be a better term) in large areas of the West Bank and East Jerusalem and also originally in Gaza, although the Gaza settlements were unilaterally disbanded by the Israelis in 2006.

The various Israeli settlements take up almost half of the occupied territories, but they are more pernicious than that. They divide Palestinian areas into tiny islands, surrounded by Israeli-controlled areas. Although there has been no mass expulsion, the process of colonisation and dispossession has gradually forced Palestinians out of the Israeli areas either into the Palestinian controlled areas, or out of the country altogether. Palestinians have found their freedom of movement progressively more restricted. If they want to leave their tiny Palestinian enclave, whether to cross Israeli territory into another Palestinian enclave, to work in Israel or to visit another country, they need to pass through Israeli-controlled checkpoints, often several of them, where they can be forced to stand in line for hours, searched, and arbitrarily refused passage. There are no airports anywhere in the Palestinian territories and they are barred from using Israeli airports, so any overseas travel must go through a third country. To make things worse, the road system criss-crossing the West Bank is segregated - the wide, well maintained roads are for Israelis only, while Palestinians are forced to travel on dangerous, pot-holed Palestinian roads.

As this security and the restrictions ramped up in response to Palestinian resistance, the Palestinian economy collapsed. There is now little in the way of local employment, and entrance to Israel to work has been increasingly restricted. Security incidents lead to frequent border closures during which no-one is allowed out. If they do get to Israel for work they are not protected by Israeli industrial laws and form a pool of cheap labour for Israeli businesses. There are massive levels of unemployment and poverty, exacerbated by poor infrastructure and shortages created by the Israeli blockade.

It's little wonder, then, that over time the conflict has become increasingly bitter and violent. The First Intifada was largely non-violent and although it was initially met by overwhelming force it eventually led to peace negotiations. Pappe's view is that the Israelis were not serious about these. The things that Israel insisted were non-negotiable - the Israeli settlements, border controls, the status of refugees, control of Jerusalem - meant that the territories merely exchanged an Israeli administration for partial control by the Palestinian Authority which became little more than a security contractor for the Israelis. As more moderate Palestinian leaders were either sidelined through imprisonment, or tarnished by involvement with the Palestinian Authority, the resistance was increasingly left to more extreme forces like Hamas and Islamic Jihad who seemed to be the only ones able to resist.

This book was written well before the current invasion of Gaza, but it was already clear that the situation had reached an impasse. The possibility of a viable Palestinian State, already remote after Israel seized 78% of the territory in 1948, continued to recede from view as more Israelis settled in the remaining country. The current area controlled by the Palestinian Authority could never be an independent State, split as it is into tiny, unconnected parcels of land with few resources and massive overcrowding. The split between Gaza and the West Bank after the 2006 Palestinian election, exacerbated by the difficulties of movement between the two territories and the ever-widening rift between Hamas and Fatah, provides an extra hurdle to the creation of a united Palestine. What options did the Palestinians have left?

***

Our media culture has trained us to see news items as discrete events. If we look for causes, they can only be immediate. If the cause is not obvious, we fall back on tropes and stereotypes. Hence, the cause of the current Israeli invasion of Gaza is understood as the Hamas attacks of 7 October, in which they killed something like 1,000 people, mostly unarmed civilians, and took around 200 hostages, some of whom they still hold. If a media outlet is to express shock and disgust at Israel's overwhelmingly disproportionate response it must also express disgust at the Hamas attack, creating a sense of equivalence between the two despite the disproportionate scale.

Our media culture has trained us to see news items as discrete events. If we look for causes, they can only be immediate. If the cause is not obvious, we fall back on tropes and stereotypes. Hence, the cause of the current Israeli invasion of Gaza is understood as the Hamas attacks of 7 October, in which they killed something like 1,000 people, mostly unarmed civilians, and took around 200 hostages, some of whom they still hold. If a media outlet is to express shock and disgust at Israel's overwhelmingly disproportionate response it must also express disgust at the Hamas attack, creating a sense of equivalence between the two despite the disproportionate scale.

What caused the Hamas attack? We have no sense of the immediate cause so we resort to the stereotype - they are an evil Islamic terrorist organisation. So of course Israel is within its rights to try and eliminate them, even if we would like them to be a bit more careful to distinguish between Hamas fighters and unarmed civilians.

This framing rests on two foundations of which we are not necessarily conscious. The first is one of Jewish exceptionalism. This has roots in the Bible and the notion of the Jews as God's chosen people, and in the 20th century was catastrophically reinforced by the Holocaust, which created a profound sense of debt to the surviving Jews. The Zionist movement, in Israel and in other Western nations, has built on this by identifying itself with Jewishness and tarring its critics with the brush of antisemitism.

The second is the steady growth and weaponisation of Islamophobia ever since the Iranian revolution of 1979, going into overdrive after the World Trade Centre bombing. This narrative presents Islamic political organisations as vicious, largely indiscriminate terrorists and any Islamic person as suspect. Any violence by Islamic activist movements is explained by reference to Islam, as no more than one would expect from them.

Seeing the current Gaza war through the lens of history, as told by Ilan Pappe and Rashid Khalidi, highlights the shallowness of this framing. Zionism doesn't equal Jewishness - Pappe himself is Jewish - and nor does Hamas equal Palestine or even Gaza. Hamas is also very different to Al Qaeda or Islamic State. It is a militant nationalist movement, dedicated to the creation of a Palestinian State governed along Islamist lines. Like all guerilla movements it operates from a position of military weakness in comparison to its occupiers, and attempts to compensate for this by operating underground, using the advantage of being embedded in the occupied territory and striking at undefended 'soft' targets.

It's easy to condemn killing and kidnapping unarmed civilians. It's more of a challenge to suggest what the combatants should be doing instead. Once you ask this question, you see that it is Israel that has all the choices. It controls the whole of Palestine. It has a powerful well-equipped army, a first world economy and the support of powerful friends, most notably the USA. It has used this power ruthlessly throughout its history - ethnic cleansing, land grabs, disproportionate responses to protest and guerilla attacks, and an uncompromising stance in any peace negotiations which ensures that there will be no peace.

The Palestinians, by contrast, have little leverage. They have an extremely constrained level of administrative control over around 12% of historical Palestine, under rules set by the Israelis. Their militias are either banned, or serve as police forces suppressing Palestinian dissent. They have few reliable supporters even in the Arab world. As a result, the Israelis are able to treat them with contempt. The choice Pappe describes, between an open prison and a maximum security one, is not one Palestinians can simply accept. Nor is it one that any ethical third party could endorse, but we all know international relations is about power, not ethics.

So what options do the Palestinian resistance have? Their only hope, and it is a slim one, is to make the occupation so uncomfortable for Israel that they open the way for a more constructive negotiation, with new options. This is a high-risk strategy, as we see. Israel has little interest in a negotiated solution because its aim has always been to occupy the whole of Palestine.

What we see now appears like a further round of ethnic cleansing. We don't know how it will end - to a large extent this is up to the Western nations which have so far continued to enable Israel. They are talking tougher now about a 'two-state solution' and stopping the Gaza massacre, but will they back their words with actions, or is it all for show? Time alone will tell.

* Lance Lawton is the friend who introduced me to Pappe. You can read some of his reflections here.

Comments