Back in early 2020, as we were all locking down for the first time and trying to work out what the hell this 'coronavirus' thing was, someone left a pile of books in the front of their house with a note saying 'please take'. I picked up a book called In Search of the Lost Chord: 1967 and the Hippie Idea by Danny Goldberg. (The title is borrowed, seemingly without acknowledgement, from a 1968 album by The Moody Blues).

Goldberg is a 50-year veteran of the US music industry, managing and publicising musical acts including Led Zeppelin, Nirvana, Bonnie Raitt, Steve Earle and The Hives. Although he wasn't strictly 'there' in 1967 - that was the year he finished school, and he entered the music business in 1968 - he was very close, and worked and socialised closely with many of its movers and shakers.Then again, having 'been there' is a somewhat nebulous idea. It's not just that, as many people are credited with saying, 'if you remember the 60s you obviously weren't there'. It's also that 1967 is a time, not a place, and a lot of things were happening in that year in a lot of different places. No-one could possibly have been in all of them. Goldberg readily acknowledges this in his introduction.

...whatever "it" was in 1967 was the result of dozens of separate, sometimes contradictory "notes" from an assortment of political, spiritual, chemical, demographic, historical and media influences that collectively created a unique energy. It should go without saying that no two people perceived the late sixties in the same way, and that the space limitations of a single volume and my own myopia require me to leave out more than I include.

The 1967 the Goldberg describes is the hippie movement centred on the Haight-Ashbury District of San Francisco and New York's East Village, although not confined to them. Here, groups of young people experimented with living communally, setting up alternative economies, creating new kinds of art, poetry and music and exploring Eastern spirituality. The centre-pieces of this movement were not big programmed music festivals like Monterey and Woodstock but 'happenings', modest-scale, free and largely unprogrammed events in which people came together and created whatever they chose within a loose framework of time and place.

Of course there was politics. They were opposed to the Vietnam War, and in favour of equality for Black people and women. But the Left politics of that time in the US was very fractured. The Black civil rights leaders were suspicious of these white middle class kids. The hard Left thought they lacked revolutionary discipline, avoiding class struggle rather than engaging in it, while the hippies were dismissive of the 'old left' as having achieved nothing. Many of the sexist norms of the wider society were perpetuated in hippie communities where women still found that they were expected to do the washing and cooking. You could think of it as a thousand flowers blooming, or else as a mess of in-fighting.

One aspect of this movement was the use of hallucinogens, something you can read about in any memoir from the 60s. In our age we are accustomed to think of 'recreational drugs' or 'party drugs' like cannabis, ecstasy or perhaps cocaine, or more serious 'drugs of addiction' like crystal methamphetamine or heroin. The former are seen to help us have a good time, the latter to perhaps make us feel good or perhaps blot out our pain for a while. But this is not what the 1960s use of hallucinogens was all about.

In the 1960s they were seen as a spiritual aid. Their use was rooted in the spiritual practices of some American First Nations people who would use mescaline, a hallucinatory drug derived from certain species of cacti, or psylocybin, drawn from a species of mushroom ('magic mushrooms'), as an aid to spiritual visions in ceremonies such as initiation and other important moments. Their use was carefully controlled and guided and took place within a long-standing spiritual framework.

In the post-war years, interest in these practices spread to the West where they were seen as having potential in psychiatry as well as spiritual awakening. The author Aldous Huxley was persuaded to try mescaline and published an account of his experience in the influential 1954 book The Doors of Perception. In 1938 Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman synthesised lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which had a very similar affect but could be made easily in a lab.

Through the late 1950s and into the 1960s Dr Timothy Leary became the main promoter of the use of hallucinogens in the US. He and his followers, including Richard Alpert, initially researched and taught at Harvard and after their expulsion from there continued their research and teaching independently. They saw these drugs as having potential to treat mental illness and reduce criminality but more importantly, as an aid to widespread spiritual awakening and subsequent social transformation.

They didn't promote indiscriminate use. They stressed the importance of what they called 'set and setting'. By 'set' they meant the mindset with which the user should approach the experience - a spirit of calm, open inquiry, peace and expectation. By 'setting' they meant the context in which the drug was used, and the people who accompanied the user. The drug would be used after careful preparation, in a safe comfortable place supervised by an experienced person who knew how to administer it, and the user would be accompanied by someone who was not using it, who would keep them safe and comfort or reassure them if they became disturbed or agitated.

1967, give or take, was the moment when this set of ideas hit the mainstream, and it became 'hip' to use hallucinogens as part of the process of expanding consciousness. But it wasn't just about drug use, it was about counter-culture. It was about exchanging war for peace, competition for cooperation, conformity for freedom to be yourself, ambition for self-realisation. This is, I suppose, the 'hippie idea'. You would free your mind, learn to think and live differently, and this would ensure not only the end of specific unjust wars but the creation of peaceful, just societies that made them unnecessary.

In the hands of these anarchic young idealists hallucinogens weren't always used within the confines of Leary and Alpert's careful psychological guidance, never mind the deeper spiritual discipline of its First Nations originators. People had 'bad trips' and careless use heightened the risks, particularly the risk of triggering psychotic illness. The drugs were also seen as threats to social order by the conservative political establishment, and in 1968 they were made 'controlled substances', so their supply and possession became criminal offences. This drew criminal organisations into the market and they were interested in profit, not spiritual awakening or psychological healing. Heroin and cocaine, which offered easier highs but were more harmful and addictive than LSD or mushrooms, flooded the scene and further muddied the original aim of awakening.

It's hardly surprising, then, that the moment passed quickly. Along with the internal divisions, the pressure from the FBI, and the infiltration of criminal drug suppliers there were plenty of people keen to cash in. No-one was trying to get rich out of the Happenings and no-one did but already by 1969 entrepreneurs were circling. Woodstock, so often seen as a high point of 'peace, love and rock'n'roll', was designed as a commercial venture and even though the event itself lost the organisers a bucket of money they earned it back many times over through the film and recordings. The 'vibe' was still there but it was already becoming hollow, as much marketing as reality. Capitalism, in the end, reasserted itself and 'normality' returned.

***

Here in Australia Meredith Burgmann and Nadia Wheatley have written a very different book about a similar time. Radicals: Remembering the Sixties was published in 2021. It taps the memories of 20 different people involved in Australian radical politics as young people in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Burgmann and Wheatley were indeed 'there', perhaps more so than Danny Goldberg. The pair met at Sydney University's Women's College in 1967 and went together to various anti-Vietnam War and anti-apartheid protests, two big issues that energised the radical movements of the late 1960s. Both of them entered university as well-behaved middle-class kids (although Wheatley has a back story of child abuse) but were rapidly radicalised through student politics and within a short time were taking part in sit-ins and getting arrested.Some of the people profiled in this book are old friends and the book often feels like a reunion as the authors, occasionally separate but mostly together, sit down with their contemporaries (now in their 70s) and chat about the old days. Many of them are familiar figures - former Labor politicians Margaret Reynolds and Peter Duncan, singer Margret Roadknight, journalist David Marr, Aboriginal activist Gary Foley, celebrity human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson, and indeed Wheatley herself who is a widely read writer. There is a strong Sydney flavour but a reasonable seasoning of Victorians and even a couple of Queenslanders and South Australians.

There's also a lot of diversity here. Some of the people are right out on the far left - Albert Langer, for instance, has been a lifelong communist, while long-standing Brisbane activist Brian Laver is an anarchist or, as he sometimes prefers, Libertarian Socialist. Helen Voysey, a prominent figure in High School Students Against the Vietnam War in the late 1960s, talks about how the movement was seeded by Resistance, a Trotskyite activist group in Sydney. But the presentation of this in the press as some sort of sinister manipulation of young minds by older radicals is hilarious when you consider that many of the Resistance organisers were still in their teens.

Others were much more mainstream and became even more so over the years. For instance, while Burgmann, Wheatley and others in this book were getting arrested and fronting court for their actions, their friend Geoffrey Robertson was carefully avoiding arrest so as not to risk his future as a lawyer. Yet as soon as he was able, he used his training to represent activists in court and continues to do so to this day. Others were taking part in University Labor clubs and ended up as Labor MPs like Margaret Reynolds, a long serving Queensland Senator and sometime Minister, and Peter Duncan, who served in both the South Australian and national parliament and introduced legislation decriminalising homosexuality as Attorney-General in the South Australian Labor Government. The journalist Peter Manning revived Sydney University's Democratic Labor Party club (for young readers, the DLP was a highly conservative Labor Party breakaway) before ending up on the Labor Left.

Then there were the Aboriginal activists, Gary Foley, Gary Williams and Bronwyn Penrith, who largely ran their own race. While the white radicals were focused on the Vietnam War, the Aboriginal ones were focused on racism, police violence and land rights, causes that the white radicals were a little slower to take up. Gary Williams remembers he saw Vietnam as a 'white folks war' and nothing to do with him, but the two cultures found common ground in the protests against Apartheid which focused on the touring Springboks rugby side. Both Foley and Williams were prominent in the Springboks protests, publishing cheeky photos of themselves in a Springboks jersey (donated by a dissenting Australian rugby player) in response to South African President Vorster saying 'no black man will ever wear a Springboks jersey'. But they also used the events to challenge their white partners to look at the racism closer to home - indeed, Williams comments that Apartheid was modelled on the system of segregation that still existed in Queensland at that time.

And of course there were women's activists like Jozefa Sobski and Margaret Reynolds and gay and lesbian people like David Marr and Vivienne Binns who had their own gender and sexual issues to fight for in addition to the causes everyone was fighting.

Despite this diversity the story that comes out of Radicals is almost entirely political. There's not a lot of drug taking or 'free love', and aside from Margret Roadknight there's not much music although there's a bit more theatre and visual art. There's a lot of protest, a lot of marching, rallying, getting arrested, organising and standing up for justice, along with ideological ferment and ongoing tensions between the different radical tribes - the Labor left, the Maoists, Troskyists and Stalinists, the Anarchists, and those who just wanted Australia to stop killing kids in Vietnam. But drugs, if they are present at all, are just for recreation.

The outlier here is Robbie Swan, the only person who talks about hallucinogens and who went on to spend many years practicing and teaching Transcendental Meditation.

Robbie agrees that his sense of outrage was strong. Seeing it all up close, he understood how society was beginning to break down and things had to change. He says that it all pushed him towards meditation and an understanding that 'there needed to be societal change, not politics as the be-all and end-all. People had to change their attitudes.' He goes on to say that he became 'more into the spiritual side of things'.

Swan aside, the prevailing narrative of Radicals is of a move away from religion or spirituality towards political action. Most of the featured activists grew up in families that were at least formally, and often very deeply, involved in Christian churches, Protestant or Catholic. For the young radicals this was part of the stultifying, conformist culture of 1950s Australia which they threw over on their path to radicalism. If religion appears it is mostly an opponent, the conservative Catholic politics of Archbishop Daniel Mannix and BA Santamaria. Only the distinguished journalist Peter Manning was able to reconcile his activism with ongoing Catholic faith, aided by radical university chaplain Fr Ted Kennedy and the writings of Dorothy Day. For the rest, it was all politics.

***

These differences are not, I suspect, about differences between the US and Australia, so much as differences between the authors. The US had its materialist left, Australia had its hippies. I've just stumbled upon authors with different outlooks.

I've been thinking as I read and revisit these two books that what we see here are two different theories of change. I don't necessarily mean this in the technical sense that the term is used in government programs but in the more general way of answering the question, 'how do you make change'.

The view in The Secret Chord could be summarised in John Lennon's lyric:

You say you want a revolution, you'd better free your mind instead.

Although Redgum only arrived on the scene in the late 1970s, the dominant view in Radicals might be encapsulated in their line.

If you don't fight, you lose.

Where should we focus our attention - on inner work and spiritual growth, or on activism for political and social change?

On the first view, it is not that activism is wrong or to be avoided, but it is viewed as superficial. You may make a small change here and there but the fundamental structure of things will continue. Even if you have a revolution, without a change of mind, a change of heart, you will just replace one form of oppression with another. This view was, of course, borne out graphically in the 20th century experiments with communism in Russia and China, which exchanged oppressive capitalism and imperialism for oppressive communism. In the late 1960s it was still possible to follow this old style communism, but as more atrocities came to light over the years this became less and less tenable, and Australia's communist party collapsed.

What the 'hippie view' risks is that you retreat into an inward-focused spirituality in which you change your mind and heart, but don't change anything else. You might, in some individualistic way, become a better happier, more peaceful person, but you leave society to go on as it is.

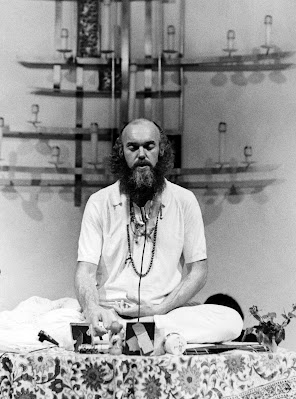

Then again, you might not. Richard Alpert, after he split from Timothy Leary, went to India and studied yoga, with his guru giving him the name Ram Dass or Servant of God. He returned to the West and spent his life teaching yoga, but he also did a lot of very practical things, like founding a charity which helped to treat blindness in India and Nepal, and was a pioneer of palliative care in the USA along with Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. Even Robbie Swan, after a period teaching meditation in Europe, returned to Australia and founded the Sex Party (now Reason) as a way of campaigning against censorship.Did it work? Well, people like Ram Dass, Wavy Gravy and others held true to their principles through the years that followed and did a lot of good. But the US, and the world, doesn't seem to have undergone a spiritual liberation in the years since. Does this mean that the strategy was wrong, or just that the countervailing forces were more powerful? And is the world a better place for having played host to those activists back then? I would like to think so.

On the second view, what matters is action and organisation. Personal spirituality is all very well, perhaps even admirable, but the important thing is getting out on the streets and into the halls of power, pushing for change and getting concrete reforms to laws, policies and systems. This is not to say that stopping a particular war, or changing a racist regime or a discriminatory law, is all there is to it. These young Marxists understood that our political and economic systems were (and are) deeply unjust, but the small immediate battles were steps along with way towards greater peace and more justice, as well as tools to build lasting movements.

How did they go? Actor John Derum, who was involved in radical theatre in Sydney and Melbourne in the late 60s and early 70s, provides a lovely reflection on his activism.

When my son, Oliver, was having a demonstration at Penrith High one day, I said to him, 'But everything we demonstrated against, we lost". And Oliver came back to me a few days later and said, "But Dad, they didn't bring back conscription, and we haven't had another Vietnam and they haven't hanged anyone else." It was great that he spotted that.

This is at least partly true. The death penalty is indeed a thing of the past, as is conscription, although the latter may have more to do with war now being so highly technologised that massive poorly-trained militias are not much use. Still, what are Afghanistan and Iraq if not 'another Vietnam' as we gear up for a newly intense Cold War with China?

Other successes share this partial nature. We have native title, anti-discrimination laws and same sex marriage but we still have inequality, racism, militarism and environmental destruction. All the organising and revolutionary doctrine of the 1960s didn't save us.But once again, did it make us better? Peter Duncan pioneered the legalisation of homosexuality, allowing people to become open about their status - and now we have same sex marriage. Gary Foley, Gary Williams and Bronwyn Penrith campaigned for land rights and anti-racism measures and founded the first Aboriginal Health Service and Legal Service in Redfern. The successors to these organisations have grown stronger in the years since, while Native Title, imperfect though it is, is a step in the right direction.

I would argue, as I tend to about all sorts of things, that neither of these theories is 'right' or 'wrong' in the black and white sense. Organising is necessary. Lobbying, court cases, taking to the streets, blockading all contribute to moving our society in a more just, more ecologically responsible direction. We can't afford the 'paralysis of analysis' while exploitation of humans and nature goes on unchecked.

But we shouldn't somehow think that these are 'the answer'. There are indeed deep spiritual maladies at the heart of our exploitive practices - greed, selfishness, insecurity, the will to power. If we leave this unattended, then the freedom fighters can easily become oppressors, the movements for liberation can fracture on their own internal politics and we will never get very far.

Ultimately, what really matters is that we keep working on both these things, and this is what both these books highlight in their own ways. Radicals begins in 2020 with Meredith Burgmann and Nadia Wheatley together in Sydney's Town Hall Square, where they have stood so many times before, joining in a Black Lives Matter rally. These two women in their 70s, still inspired by the political lessons they learned 50 years ago, present an inspiring vignette of perseverance and deep radicalism which keeps on keeping on. We see this played out in so many of the stories in the book as people move on from their naive 60s radicalism to lifelong ventures in politics, law, journalism, education, community organisations and the arts, working for a better world in their own spheres.

The movement described in Lost Chord is in many ways more ephemeral. The people dissipated and although many of them (like Ram Dass) continued to do good work others quickly faded from view. Yet 50 years on it continues to fascinate and attract, a time and ethos that we often yearn for but find impossible to realise. And elements of the hippie era continue. People like the Hog Farm Collective founded by Wavy Gravy were the forerunners of communal movements that still flourish today - land cooperatives, intentional communities, movements for simplicity - and these provide much of the deep grounding for the environment movement. And, of course, the music of that era continues to inspire. Even the use of hallucinogens as spiritual aids still has its disciples.

Did any of these people 'succeed'? Yes they did. They made the world a better place. But they didn't fix everything. This is why they, and we, are still working on it.

Comments