A little after 8.00pm on Monday, 15 June, Noel Henry was riding his bicycle to his home in the Adelaide suburb of Kilburn when he was pulled over by the police. They told him they suspected him of being in possession of drugs, and ordered him to put his hands on his head so they could search him. According to the police statement released the next day, he 'originally was compliant and after a short time he began to refuse. Police attempted to arrest the man who resisted and a struggle ensued.'

The noise of this struggle alerted his friends who came out of the house. Some of them filmed parts of the incident and subsequently posted their films on social media. They show three police officers holding Henry on the ground, one of them hitting him, and his head being forcibly pushed down onto the concrete footing of the fence they have pinned him against. All this while his friends yell at the police to 'get off his head' and 'let his head up', while others attempt to intervene, only to be pepper-sprayed. Eventually Henry was arrested and taken to the Kilburn police station, where he was charged with hindering police, resisting police and property damage - apparently a police body camera was damaged during the struggle. He was released the next morning, with minor injuries, and the subsequent police statements are ambiguous about whether they will pursue the charges.

These are the raw details, but it is important to look at the detail here and probe a little beyond the bald facts. The first thing to note is that Noel Henry is Aboriginal. The second is that the police were in the neighbourhood responding to 'an alleged high risk domestic violence matter where a woman was taken to hospital'. Henry was riding his bicycle near the address of their call-out, although as far as I can tell he had no connection to the incident they were investigating. I don't suppose the police could have been expected to know that, and so it made sense that they stopped him to find out. Other witnesses have suggested he was initially stopped because he was not wearing a helmet. But look what happens next. The police say they suspected he was carrying illicit drugs and they searched him. Wait, what? Weren't they responding to a domestic violence incident? What led them to have this suspicion? Looking at the subsequent charges it was clearly unfounded. At what point did they realise he had no drugs? They don't say.

The second thing to note is the subsequent escalation. While Henry initially consented to be searched, at some point he decided he'd had enough, and refused to cooperate further. At this point, the police resorted to force, and before long there were three policeman holding him down while he struggled to escape. This was clearly a violent struggle and it is not surprising that reports afterwards indicate Henry was injured, as was one of the police. According to one of the witnesses, the entire incident lasted about 45 minutes, and Henry was on the ground for about 20 of these. For part of these 20 minutes he was not moving and his friends feared he was unconscious.

Meanwhile, remember that 'high risk domestic violence matter'? During this 45 minutes, what was going on with that? While the police were inexplicably searching someone for drugs and pinning him to ground, were the woman and her children safe? Where was the perpetrator of this serious violence? Nothing in the police report or the media answers that question and I wonder if any of the journalists thought to ask.

It is of course no accident that this happened to an Aboriginal man. One his friends who witnessed the incident explained.

(Doris) Kropinyeri said other Indigenous people in the Kilburn area were regularly approached by police.

“Me and my friends have been walking down the street in the middle of the day and police will pull us over and ask us where we are going,” she said.

“They said they suspected he had illicit drugs, that’s always the case, they seem to think that we are all drug users here, every Indigenous person in the Kilburn area.”

In a final detail, his friends notified the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement, whose representative went to the Port Adelaide watch-house in the capacity of his legal representative. The police appeared to be uncooperative, refusing to tell his representative whether he had medical treatment (the police commissioner subsequently suggested he had been offered this but refused it) and telling them he had not been given bail because he hadn't asked for it.

To me, this incident is the whole story of Aboriginal deaths in custody told in one incident, but fortunately without the death. Let me step you through it.

1. An Aboriginal man is stopped on the street, even though he doesn't appear to be doing anything wrong (aside, perhaps, from riding his bicycle without a helmet) and is accused of possessing illicit drugs, an accusation which turns out to be untrue. There was quite possibly no need to stop him at all, but if they did need to, say if they thought he had some connection with the domestic violence incident they were supposed to be attending, then it would have made sense for them to skip the drugs bit and ask him about that.

2. When the man decides that he is being treated unjustly and refuses to cooperate further, the police decide to arrest him, and insist on their way by forcing him to the ground and holding him down for an extended period. What were they arresting him for? Did they have any evidence that he had committed a crime? Clearly not, given they didn't charge him with one - his charges all relate to his conduct after their attempted arrest.

3. He is then held overnight (not bailed) and not given medical assistance despite being injured. These are both common factors in deaths in custody, and both were completely avoidable.

Fortunately Noel Henry escaped with only minor injuries - I say fortunately because since 1991 over 430 Aboriginal people have died in prison or police custody and some of these have been in similar circumstances. In 2004 on Palm Island, Mulrunji Doomadgee had his spleen ruptured in a similar violent arrest for a trivial offence and died in the watch-house without anyone calling a doctor.

Meanwhile, this piece of apparently routine harassment and subsequent escalation seems to have taken priority over a serious incident of domestic violence. Because domestic violence is not that important, right?

It's not clear what the South Australian police leadership think of this incident, but perhaps they are not entirely happy. The two officers who were mainly responsible have been 'placed on administrative duties' while an internal investigation takes place. But we have heard about these internal investigations before. It is rare for a police officer to be sacked, or even demoted, as a result of one. In the case of Mulrunji Doomadgee, the officer who killed him, Snr Sgt John Hurley, was charged with manslaughter but acquitted. Key pieces of evidence were cleaned up before investigators arrived and the investigators spent their time on the island drinking and hanging out with Hurley and his associates. No-one was disciplined over this cover-up. Hurley kept his job in the Queensland Police for over a decade. It took two further incidents of violence, both against non-Aboriginal suspects (neither of whom died) for him to finally be sacked.

***

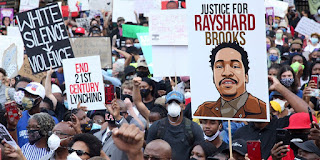

Another thing that highlights the extent of Noel Henry's good luck is a disturbingly similar incident that occurred three days earlier on the other side of the world, in Atlanta, Georgia. Rayshard Brooks, a young African-American man, was asleep in the front passenger seat of a car that was pulled up, driverless, in the drive-through of a fast-food restaurant. It's not clear how he got there and why the car was pulled up where it was, blocking customers from using the drive-through. Perhaps if he had been in the car-park a few metres away he would still be alive now. As it was, the police arrived.

The encounter was initially peaceful and routine. A single police officer arrived, woke Brooks up and asked him to move his car into the car-park, which he did. Then he got out of the car and the police officer noted that he seemed to be drunk and called for a colleague to help him. The two of them conducted a 'sobriety test' which included a breathalyser, which showed him to be over the legal limit for driving. He was perfectly cooperative with the police for the 40 minutes all this took, and he was unarmed.

Let me pause at this point to look at this. So far in the story, it is not clear that Rayshard Brooks has broken the law. He may have. After all, his car got there somehow, so perhaps he drove it there. But when the police arrived he was not driving the car, he was asleep in the passenger seat. The only time he drove the car, to their certain knowledge, was at their direction, to shift it a few metres out of the drive-through. Aside from the unfortunate choice of parking place, he was in fact doing just what the police and road safety authorities ask us all to do when we are too drunk to drive - sleep it off, and drive later when we are sober. He does not seem to have been a danger to anyone.

Nonetheless, the police decided to arrest him and the situation rapidly went from routine to catastrophic. Brooks refused to accept arrest and struggled violently with the two officers. They attempted to pin him to the ground, and one of them tasered him repeatedly to try and stop his struggles. He managed to wriggle out of their grip, grabbed one of the officers' Tasers and ran off, discharging the Taser in their general direction (but not coming close to hitting them) as he ran. In response, one of the officers dropped the taser he was holding, drew his pistol, and shot Rayshard Brooks three times. Brooks died of his gunshot wounds.

There are so many things wrong with this incident, and they start well before the fatal shots. They are similar to the things that went wrong in Noel Henry's case.

1. The police did, in fact, have a responsibility to make sure that he didn't drive while drunk, but they were not obliged to arrest him. There were other ways to stop him from driving. They could simply have told him not to, and taken his word that he would go back to sleep in the car and drive home in the morning. If they were worried about him lying to them, they could have confiscated his keys. They could have confiscated the keys and locked the car with him outside it, and then left him to fend for himself. They could have offered to drive him somewhere. Brooks suggested his own solution - his sister lived nearby, he said, he would walk to her house and come back to get the car in the morning. Perhaps they could have given him a lift there. This would have kept everyone safe - him, all the other road users and, incidentally, themselves.

2. Then, of course, there is the actual shooting, which is pretty much impossible to justify. Although Brooks had their Taser - a non-lethal weapon - he was running away, not threatening them. They could simply have let him run. They knew who he was, and where he lived. They had his car, and theirs. They could even have followed him in their car and picked him up when he ran out of breath and the adrenaline rush subsided. Instead, the officer seemingly didn't even think before drawing his gun and firing.

Unlike the South Australian police, it is pretty clear what the Atlanta police command think of this incident. Both officers have been sacked, and the man who fired the gun, Officer Garrett Rolfe, has been charged with murder. This has a long way to go, and we should not get our hopes up at this stage. Of the many US police officers who have faced charges over killing members of the public, including unarmed ones who were not threatening them in any way, only one has been convicted - ironically Mohamed Noor, a black policeman who killed Justine Damond, a white Australian woman who had called the police in response to a suspected domestic violence incident in her neighbourhood.

***

The sad thing about both of these incidents is that they occurred after the death of George Floyd and during the resulting mass protests in both the US and Australia. These events were the top items on the nightly news here in Australia as they were in the USA. The police officers involved must have been aware. Why were they not being doubly careful and thoughtful in the way they dealt with black people in the community?

But it is easy to just lay the blame at the feet of the police involved. Certainly if you kill someone, or beat them up, there should be consequences. But the fact that this happens repeatedly, across both our countries and many others, indicates that something deeper is going on. We need to change systems and cultures as well as prosecuting some individuals.

Of course, the men who ended up in the watch-house (Henry) or dead (Brooks) were part of oppressed groups - Aboriginal Australian, African American. In our respective countries, these two population groups are massively over-represented in our prisons and justice systems. Some people have said to me, in recent weeks, that this is because they commit more crime. If they didn't commit crimes, they wouldn't be in prison. This is partly true but only a small part of the story. What stands out in both these stories is that the two men were not in fact committing crimes. Noel Henry was riding his bike home. Rayshard Brooks was sleeping in his car. One had the misfortune of being near where a crime took place, the other had parked in an inconvenient place. It would be hard not to conclude that the subsequent police response was driven in part by their race.

A second thing to notice is that in both situations the process of investigation and arrest took precedence over concern for the safety of either the person concerned or other members of the public. The South Australian police were supposed to be attending a domestic violence incident, but they allowed themselves to be diverted by the notion of finding out if Noel Henry was carrying illicit drugs, and then arresting him for refusing to cooperate. The safety and wellbeing of the woman and perhaps her children took a back seat, not to mention Henry's own wellbeing. In Atlanta, once the police had established clearly that Rayshard Brooks was too drunk to drive their priority was not to ensure he got home safely and without injuring anyone else, it was to arrest him, presumably for being drunk in charge of the vehicle in which he was sleeping.

I wonder if this is a product of how success is measured in the police forces of the two places. Are they rewarded for making arrests, but not for getting people home safely? Certainly in the past decade or two we have seen a steady growth of 'law and order' policies which favour arrests, charges and jailing people over prevention and rehabilitation of offenders. In the US, especially, many places have laws which allow police to stop and search people without any reason, and a number of categories of trivial and virtually non-existent crimes on which they can be arrested. You will not be surprised to hear which racial group is most targeted by these laws. In Australia one of the most common reasons Aboriginal people, and other poor people, end up in prison is unpaid fines. This means a trivial offence such as travelling on public transport without a ticket can gradually escalate into a huge fine with charges for interest, court costs and so forth which the person has no chance of ever paying, and which can only be expunged by a stint in jail. Surely we can do better!

A final thing to note here is that once the process began, there seems to have been an imperative that the person must not get away, that they must be subdued and brought into custody. Remember that these are not men charged with serious crimes, or posing a threat to society. Yet once the police had started down the enforcement track there was no escape hatch, no way for them to pull back, even when going on required risking (and in Brooks' case taking) their lives.

In 1991 Australia held a Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody which made over 300 recommendations. Some were implemented, most were not, and even those that were are often now honoured in the breach. More recently, the Australian Law Reform Commission investigated the question and came up with a more modest list of 35 recommendations. As far as I know no Australian government, national, State or Territory, has yet taken up its recommendations. I don't know the US scene so well, but I have not doubt people have proposed similar solutions there as well.

If you ever think that racism is a thing of the past ask yourself, why does this keep happening? Why do Aboriginal people, and African Americans, feel so strongly about this that they will turn out in huge numbers in the middle of a pandemic? And why do our governments not leap into action, but instead keep doing the same things they have always done? That is racism. I like to think we can do better.

Comments