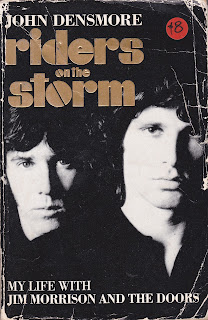

Last year I wrote a review of The Doors which for some reason is the most visited post on this blog, perhaps because it includes a couple of pictures of Jim Morrison. Anyway, on the plane home from the Kimberleys I had a read of John Densmore's Riders on the Storm, published in 1990.

For those who missed it, the Doors represent the dark side of the late 60s and early 70s. Their songs portray a world of despair, confusion and nihilism far removed from the peace, love and harmony of Woodstock, where they refused an invitation to perform. Their live performances, fuelled by singer Jim Morrison's erratic moods and alcohol addiction, were unpredictable and at times dangerous. Their brief career ended in 1971 with Morrison's death, apparently from a heroin overdose, in a Paris hotel room.

For those who missed it, the Doors represent the dark side of the late 60s and early 70s. Their songs portray a world of despair, confusion and nihilism far removed from the peace, love and harmony of Woodstock, where they refused an invitation to perform. Their live performances, fuelled by singer Jim Morrison's erratic moods and alcohol addiction, were unpredictable and at times dangerous. Their brief career ended in 1971 with Morrison's death, apparently from a heroin overdose, in a Paris hotel room.

Densmore, the Doors' drummer, is so far the only member of the band to tell his story. This may be because the story is not pleasant, and perhaps all of them are more than a little ashamed of what happened.

This certainly seems to be the case for Densmore. He is justly proud of their musical acheivements, both in the studio and on stage, and describes both at rather tedious length. Yet there is a lot more regret here than pride.

Despite years of therapy both before and after Morrison's death, Densmore doesn't provide us with a lot of psychological depth. He sticks with the day to day details. Yet it is easy to read between the lines. Morrison's dominance of the Doors was not merely for public consumption. Although he knew little about music he dominated proceedings in the way only a true psychopath can. When he was at peace, they were at peace. When he was troubled, they were troubled. When he was roaring drunk, their performances staggered. When he was sober, they rocked. When he died, they died

Not that the rest of them were angels by any means. The use of LSD was pretty much shared, as were other aspects of the rock star life. Yet the other three were stable, professional, relatively phlegmatic musicians. Left to themselves, they would have had serene, low profile lives as session players and night club sidemen. Add Morrison to the mix, and they exploded, then flamed out with him.

Take this story from before they got famous. Densmore has left Morrison at the home of a female acquaintance, gone out for some drinks and then returned.

The door opened as I knocked.... I pushed it open the rest of the way and saw Jim standing in the living room, holding a large kitchen knife to Rosanna's stomach. A couple of buttons popped on her blouse as Jim twisted her arm behind her back....

"What do we have here?" I exclaimed, trying to defuse the tension. "Quite an unusual way of seducing someone, Jim."

Jim looked at me with surprise and let Rosanna go. "Just having a little fun."

Rosanna's expression changed from fear and rage to relief. Jim put the knife down.

I'm in a band with a psychotic. I'M IN A BAND WITH A PSYCHOTIC!

I'm in a room with a psychotic.

"Well, I've gotta go....Do you wanna ride?"

"Naw."

I made a hasty exit. I was worried about Rosanna but I was more worried about myself. There was definitely sexual tension in the room as well as violent tension. That's how I rationalized leaving.... I wanted to tell someone, my parents, anyone...but I knew I couldn't.

This story says it all, really. As Morrison spiralled further and further out of control, Densmore and the others firmly looked the other way and played on. Now Densmore looks back with regret. Should he have done more? Would it have made any difference if he had? In a number of letters to Morrison he tries to work out this classic survivor guilt, airing both his regret at having done nothing, and his anger at Morrison for being such a dick.

Nor does it stop there. Densmore's affection for Robbie Krieger is obvious, their friendship pre-dating the Doors and surviving the band's demise. Krieger provides an endorsement on the book cover. Ray Manzarek pointedly does not. The tension between Densmore and Manzarek is hardly less visible than Densmore's anger and grief over Morrison, but its reasons are much harder to find.

Morrison was clearly a pain in the neck. Manzarek, on the other hand, comes across as the ultimate professional. He was the oldest of the four, had a stable relationship throughout the band's career and beyond, provided the musical glue that held them together, and even rescued them by singing when Morrison was too wasted to perform. So why are he and Densmore no longer speaking?

Densmore doesn't quite come out and say it, but it seems to me that he blames Manzarek for Morrison's death. He points to him being the one who was closest to Morrison and had brought them all together, the closest thing Morrison had to a father figure once he rejected his real (and it seems probably abusive) military dad. Why didn't Ray do something? And why, after his death, did he persist in presenting such a rosy picture of the band?

Densmore clearly feels let down, but its just as clear that he is making Manzarek bear some of his own guilt. Because he, Densmore, also did nothing. Nor did his mate Krieger. For five years all three played the classic part of co-addicts, aiding and abetting Morrison's self-destruction. Densmore is torn because he knows he got rich and famous on the back of Morrison's genius, yet stood by and idly watched him destroy himself. Right from the beginning he saw that something was seriously wrong and he walked away.

When we listen to the Doors, we should remember this pain. We enjoy, and benefit from, Morrison's genius. At our distance his dark vision is romantic and challenging. Yet from close up his addiction and psychosis left a trail of damage which 20 years later had still not healed.

What happened to Rosanna? How many other women found themselves alone in a room with Morrison in a similar mood? If we were Densmore, what would we have done?

For those who missed it, the Doors represent the dark side of the late 60s and early 70s. Their songs portray a world of despair, confusion and nihilism far removed from the peace, love and harmony of Woodstock, where they refused an invitation to perform. Their live performances, fuelled by singer Jim Morrison's erratic moods and alcohol addiction, were unpredictable and at times dangerous. Their brief career ended in 1971 with Morrison's death, apparently from a heroin overdose, in a Paris hotel room.

For those who missed it, the Doors represent the dark side of the late 60s and early 70s. Their songs portray a world of despair, confusion and nihilism far removed from the peace, love and harmony of Woodstock, where they refused an invitation to perform. Their live performances, fuelled by singer Jim Morrison's erratic moods and alcohol addiction, were unpredictable and at times dangerous. Their brief career ended in 1971 with Morrison's death, apparently from a heroin overdose, in a Paris hotel room.Densmore, the Doors' drummer, is so far the only member of the band to tell his story. This may be because the story is not pleasant, and perhaps all of them are more than a little ashamed of what happened.

This certainly seems to be the case for Densmore. He is justly proud of their musical acheivements, both in the studio and on stage, and describes both at rather tedious length. Yet there is a lot more regret here than pride.

Despite years of therapy both before and after Morrison's death, Densmore doesn't provide us with a lot of psychological depth. He sticks with the day to day details. Yet it is easy to read between the lines. Morrison's dominance of the Doors was not merely for public consumption. Although he knew little about music he dominated proceedings in the way only a true psychopath can. When he was at peace, they were at peace. When he was troubled, they were troubled. When he was roaring drunk, their performances staggered. When he was sober, they rocked. When he died, they died

Not that the rest of them were angels by any means. The use of LSD was pretty much shared, as were other aspects of the rock star life. Yet the other three were stable, professional, relatively phlegmatic musicians. Left to themselves, they would have had serene, low profile lives as session players and night club sidemen. Add Morrison to the mix, and they exploded, then flamed out with him.

Take this story from before they got famous. Densmore has left Morrison at the home of a female acquaintance, gone out for some drinks and then returned.

The door opened as I knocked.... I pushed it open the rest of the way and saw Jim standing in the living room, holding a large kitchen knife to Rosanna's stomach. A couple of buttons popped on her blouse as Jim twisted her arm behind her back....

"What do we have here?" I exclaimed, trying to defuse the tension. "Quite an unusual way of seducing someone, Jim."

Jim looked at me with surprise and let Rosanna go. "Just having a little fun."

Rosanna's expression changed from fear and rage to relief. Jim put the knife down.

I'm in a band with a psychotic. I'M IN A BAND WITH A PSYCHOTIC!

I'm in a room with a psychotic.

"Well, I've gotta go....Do you wanna ride?"

"Naw."

I made a hasty exit. I was worried about Rosanna but I was more worried about myself. There was definitely sexual tension in the room as well as violent tension. That's how I rationalized leaving.... I wanted to tell someone, my parents, anyone...but I knew I couldn't.

This story says it all, really. As Morrison spiralled further and further out of control, Densmore and the others firmly looked the other way and played on. Now Densmore looks back with regret. Should he have done more? Would it have made any difference if he had? In a number of letters to Morrison he tries to work out this classic survivor guilt, airing both his regret at having done nothing, and his anger at Morrison for being such a dick.

Nor does it stop there. Densmore's affection for Robbie Krieger is obvious, their friendship pre-dating the Doors and surviving the band's demise. Krieger provides an endorsement on the book cover. Ray Manzarek pointedly does not. The tension between Densmore and Manzarek is hardly less visible than Densmore's anger and grief over Morrison, but its reasons are much harder to find.

Morrison was clearly a pain in the neck. Manzarek, on the other hand, comes across as the ultimate professional. He was the oldest of the four, had a stable relationship throughout the band's career and beyond, provided the musical glue that held them together, and even rescued them by singing when Morrison was too wasted to perform. So why are he and Densmore no longer speaking?

Densmore doesn't quite come out and say it, but it seems to me that he blames Manzarek for Morrison's death. He points to him being the one who was closest to Morrison and had brought them all together, the closest thing Morrison had to a father figure once he rejected his real (and it seems probably abusive) military dad. Why didn't Ray do something? And why, after his death, did he persist in presenting such a rosy picture of the band?

Densmore clearly feels let down, but its just as clear that he is making Manzarek bear some of his own guilt. Because he, Densmore, also did nothing. Nor did his mate Krieger. For five years all three played the classic part of co-addicts, aiding and abetting Morrison's self-destruction. Densmore is torn because he knows he got rich and famous on the back of Morrison's genius, yet stood by and idly watched him destroy himself. Right from the beginning he saw that something was seriously wrong and he walked away.

When we listen to the Doors, we should remember this pain. We enjoy, and benefit from, Morrison's genius. At our distance his dark vision is romantic and challenging. Yet from close up his addiction and psychosis left a trail of damage which 20 years later had still not healed.

What happened to Rosanna? How many other women found themselves alone in a room with Morrison in a similar mood? If we were Densmore, what would we have done?

Comments